We don’t build towers but we’re experts at designing, deploying and maintaining technology systems that rise to the top of them. Spend a day with a Commenco tower crew and you’ll understand why demand for their work is soaring and what makes their skills so hard to find.

One Tower Among Hundreds

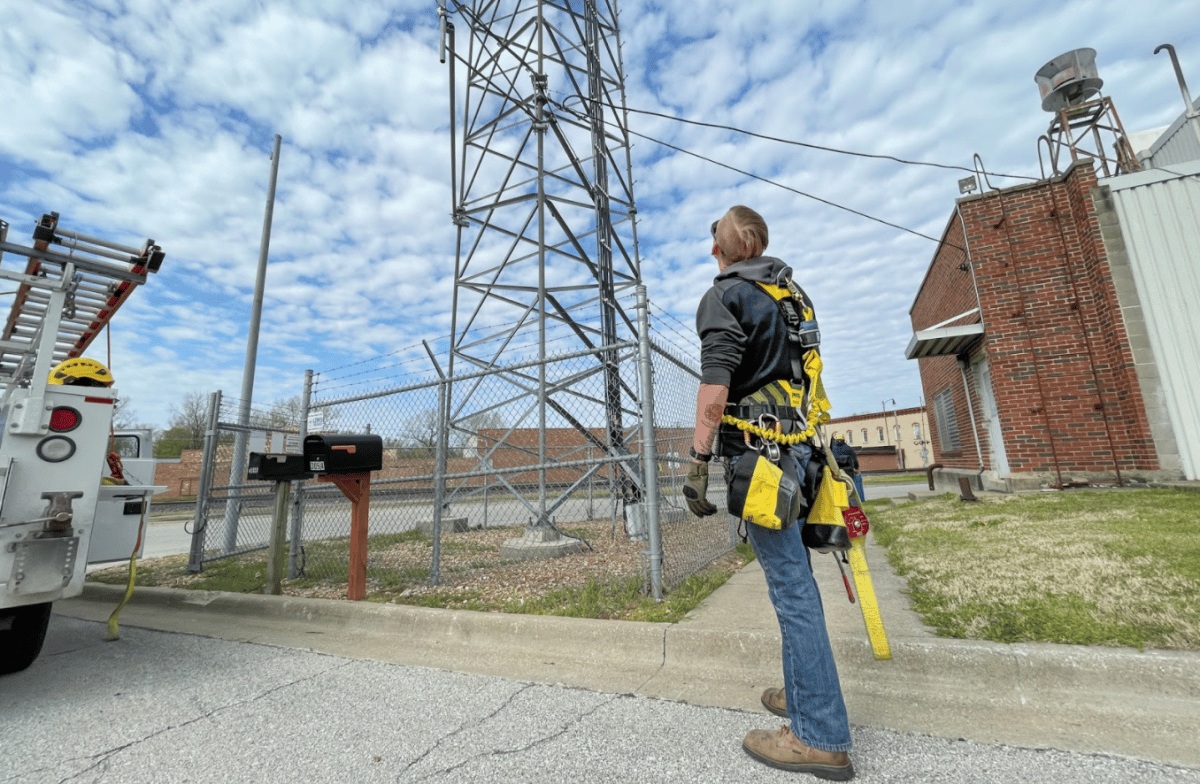

Bright and early one Monday morning, the sky was partly cloudy, the wind was fairly calm and conditions were right for a climb up a communications tower on the prairie just outside of Kansas City. Towers can reach several hundred feet into the sky and require a circle of support cables anchored in the ground, but the job on this day involves a structure small enough to support itself.

“It’s only 150 feet, but that’s high enough for something to reach 60 miles per hour by the time it hits the ground,” emphasizes veteran climber Jim Outman. “Every climb is dangerous. We never forget that.”

Good luck finding a climber with more experience than Outman. He’s been at it over three decades and is as comfortable clinging to steel high up as he is standing on the ground. Outman doesn’t climb as much as he used to, taking on more of a supervisory role these days to help train new climbers. But there are hundreds of towers in the Kansas City area and he’s been up most of them hundreds of times.

“When you get up over 300 feet, things change. They become twice as hard. There’s a cumulative effect of the weight of the gear and the mental challenge that starts to really add up at that point. When you get to 500 feet, you might say it gets three times harder.”

Outman has visited this particular tower many times, estimating its age at about ten years and recognizing the subtle remains of the tower it replaced across the street. All that’s left there is a small, crumbling concrete platform where Outman stepped off the ground more times than he can count.

“In the old days, way back, it was pretty much climbers and leather straps used to crawl up and down the legs of the towers. Things are so different now and safety has become priority one. And there are so many more towers. They’re a growing web of infrastructure. You’ve got everything from sophisticated lighting to communications technology up there, and it’s constantly changing to keep up with new demands.”

Mission to the Top

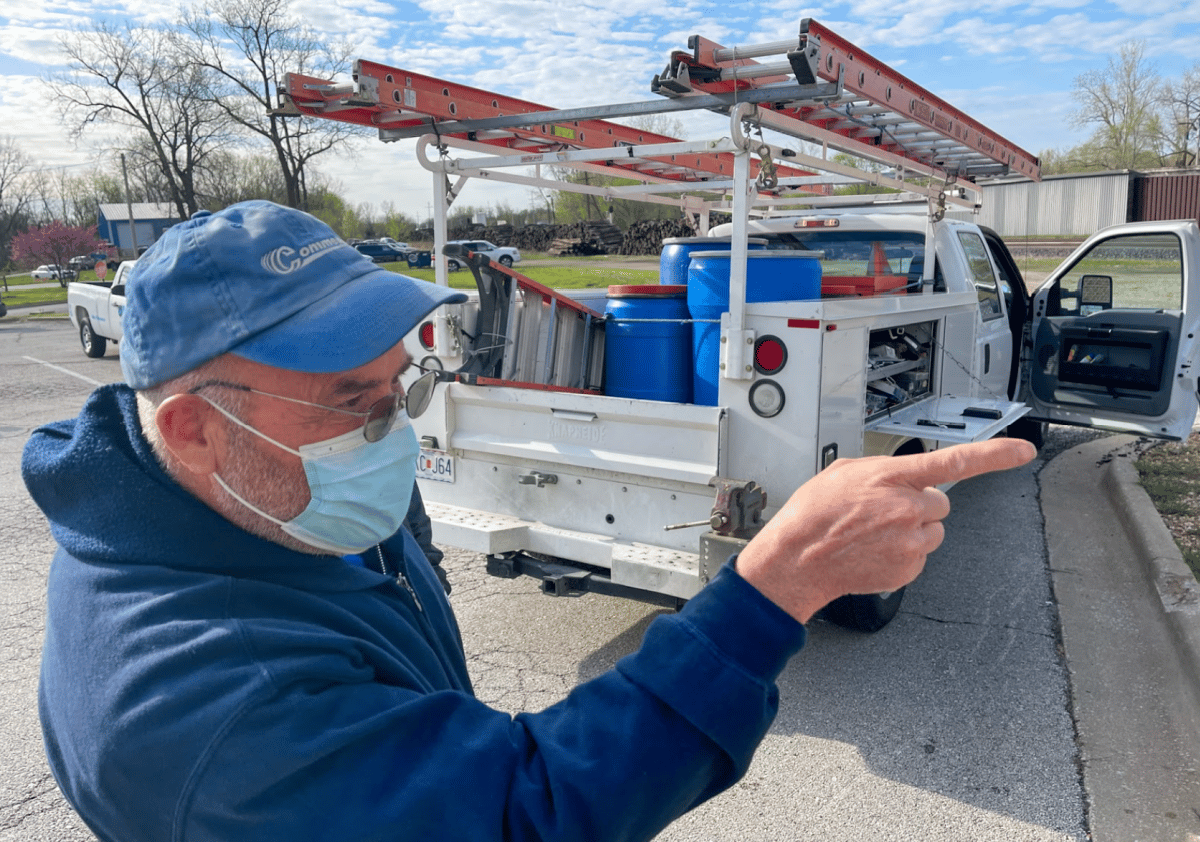

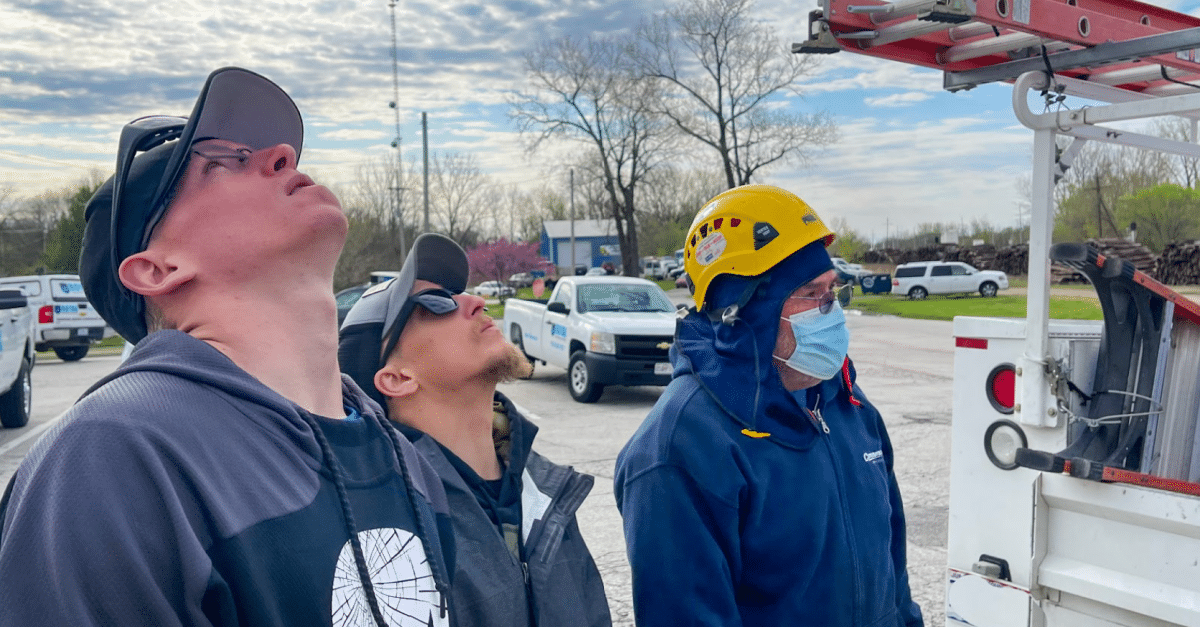

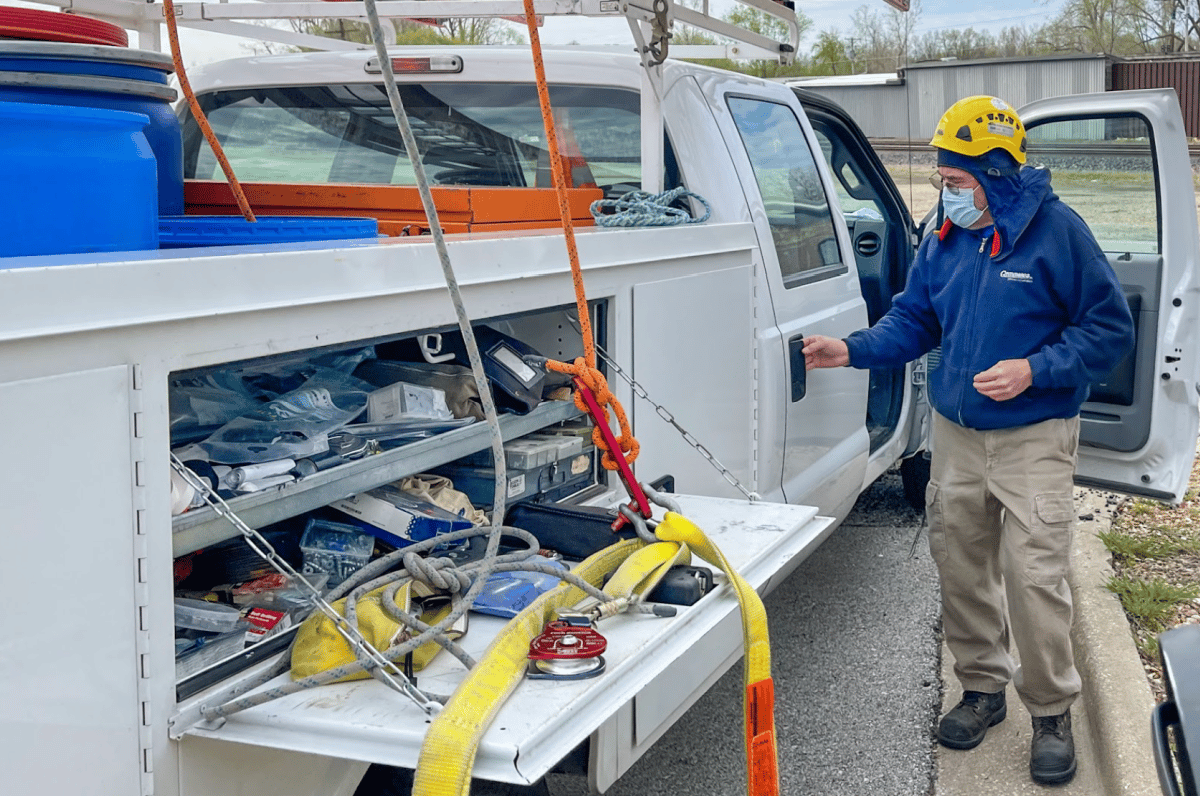

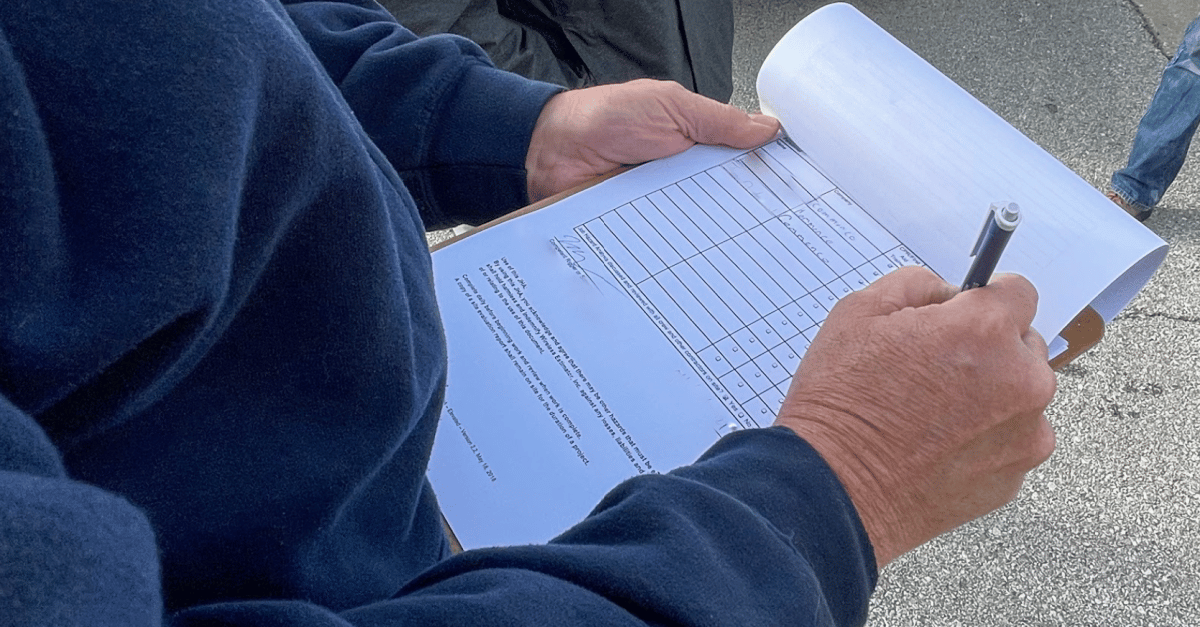

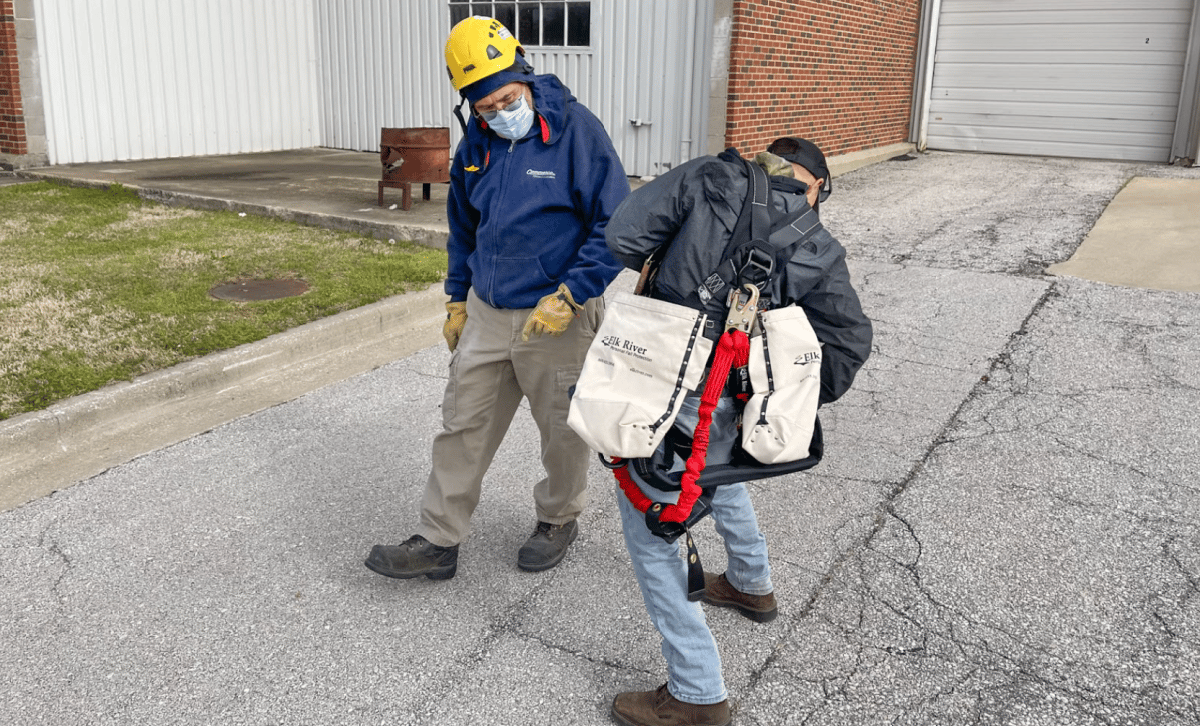

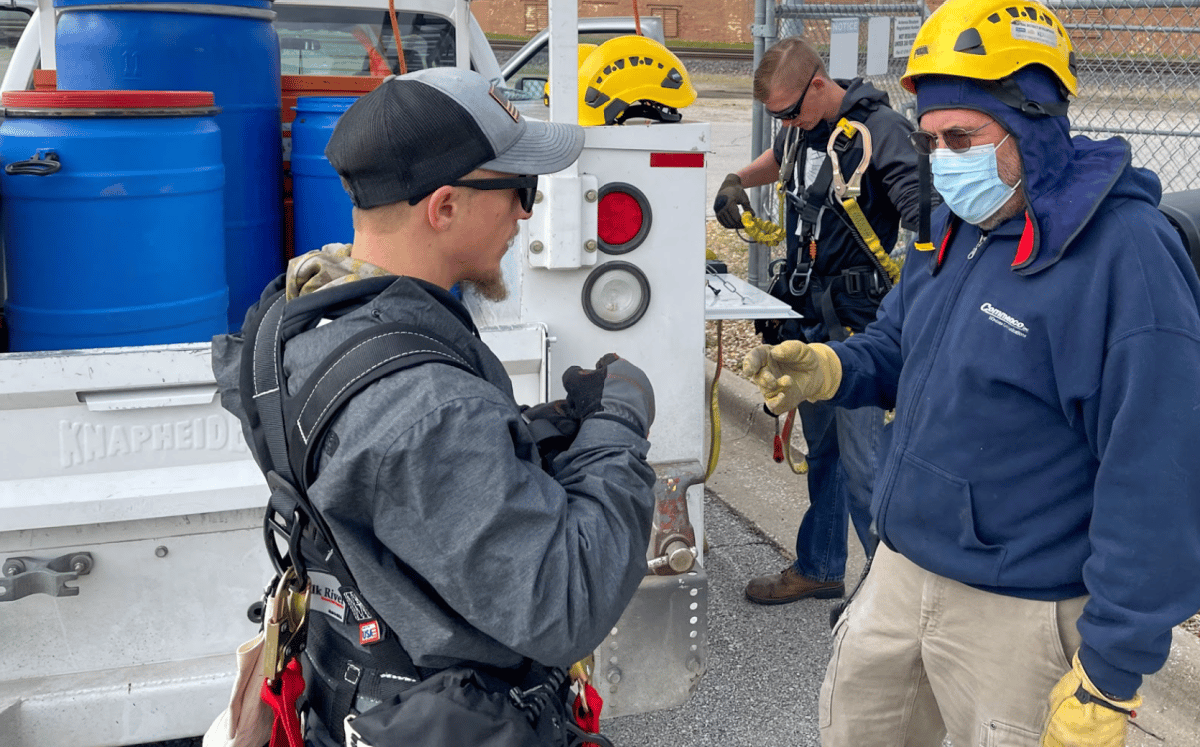

The crew’s purpose on this particular day is to inspect the tower up and down. The service is part of maintenance responsibilities aimed at preventing technology disruptions that could threaten anything from routine police calls to emergency fire response. When the Commenco truck pulls up, climbing preparations begin and seem to last almost as long as the climb itself. Outman is supervising technicians Noah Campbell and Matt Kendall as the crew pulls open side panels on the vehicle and takes inventory of their hardware.

“Safety is everything from start to finish,” says Outman, clarifying what becomes second nature to Commenco climbers. “Setting up is about preventing things from going wrong. We’re accounting for all of our equipment and making sure we have everything we need to do things safely and do them right.”

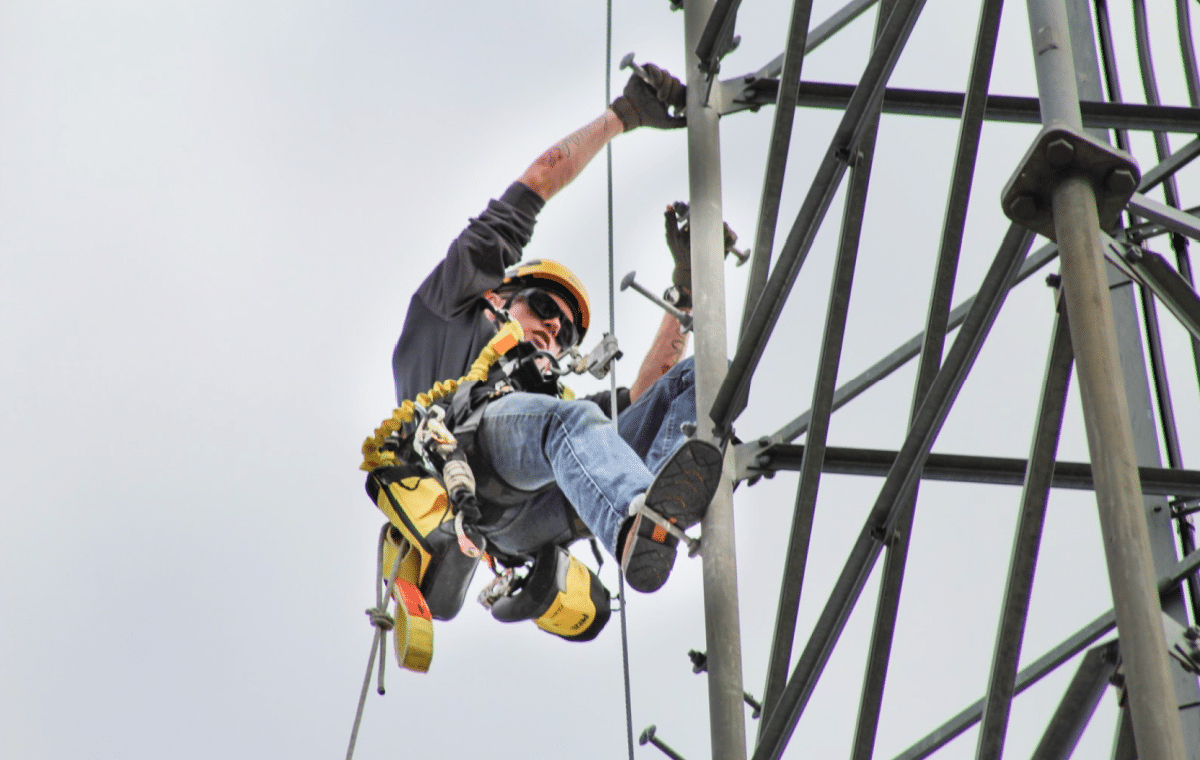

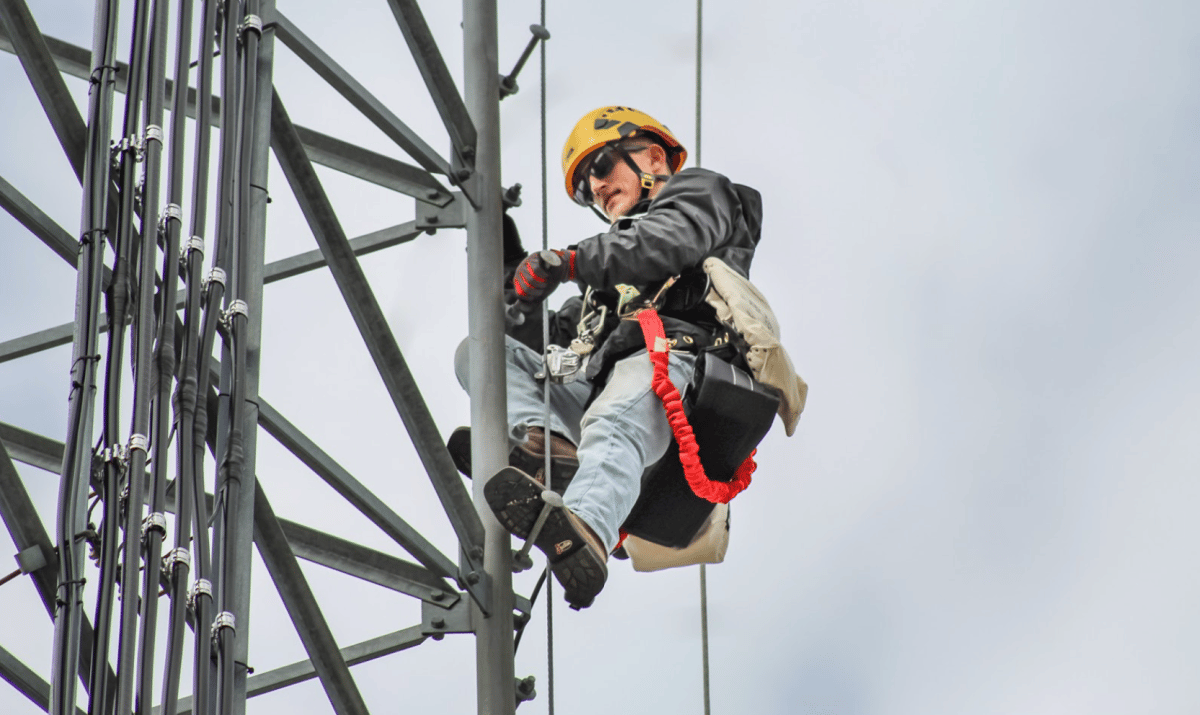

Campbell and Kendall suit up from head to toe with specialized climbing gear strategically placed for easy access at dizzying heights. Harnesses, clips, helmets, gloves and radios are included in what amounts to an elaborate industrial uniform. Climbing these towers is hard enough. Imagine carrying all that gear with you.

“The gear can add as much as 40 pounds,” says Outman, circling a member of his crew, looking closely for anything out of place or missing. “You need all of it. It’s just part of the job and you get used to it.”

Climbing with 40 extra pounds? It’s no secret that tower climbers are some of the strongest people you’ll ever meet. Outman says he put on over 30 pounds of muscle in the first year of his climbing career. Gear weight creates much of that strength. The rest comes from the climbing itself.

“Sometimes we still need the help of the strap,” says Noah Campbell, looking down at his waist, clicking and snapping pieces into place. “I’ve wrapped it around the leg of a tower and wiggled up hundreds of feet. It’ll tire you out, for sure.”

Campbell is an especially rare talent. Climbing towers feels very familiar to a Marine Corps veteran who served as a parachute rigger, packing cargo loads, tying them to parachutes, and dropping them from airplanes. He’s hooked up and parachuted everything from water supplies to vehicles. He’s jumped, too.

“I love it. It’s what I know,” Campbell remarks, smiling beneath dark glasses and a bright yellow helmet. “None of this scares me. It’s just another day on the job. I’ve jumped from military planes so many times. Climbing way up these towers is sort of like that. I’ve always been good with technical tasks and using my hands. And I like working in the sky.”

Campbell is first up. As he steps onto the tower, Outman notes his unusual qualifications. “Climbers typically come right out of high school or from a different line of work. Noah has a very specific military background that not only gives him strong core skills, he’s also very disciplined and mission oriented. A good work ethic.”

In his first year of climbing, Campbell has scaled towers hundreds of times, logging about nine miles so far in his estimation. Matt Kendall is following his lead. Kendall is also a military veteran with less climbing experience, but all of the same passion. “I grew up in Leavenworth and served for nine years. This work is a good fit for me following my service.”

As Campbell and Kendall head up, Outman keeps close watch from the ground, aligning ropes and staying in contact via two-way radio. The climbers are attached to the tower at all times, which ensures safety but makes for slow going. Their movements are careful and methodical, but still look unsettling to the untrained eye. Campbell says he rarely feels any fear.

“We never climb in dangerous weather conditions, but when we’re up there and a wind gust suddenly tries to push you away from the tower, that’s not a good feeling. But it’s nothing you can’t handle. Meanwhile, you’ve got these views that are just amazing every day. Nobody can see the world like we do unless you’re in an airplane or something. It’s really amazing.”

Drones and even satellites are trying to find roles in tower service work, but nothing really beats the hands-on, eyes-on benefit of a trained technician working directly on a tower, installing, analyzing and repairing technologies towers are built to support. A simple inspection climb draws heavily on human judgment sharpened by human experience. Technicians literally feel for loose connections, check weather proofing materials, secure cabling, and evaluate stressed connections. Two-way radios immediately relay findings to the ground and become a lifeline if something doesn’t go quite as planned.

One-of-a-Kind Feeling of Success

The climb back down is as slow as the climb up. Step-by-step and clip-by-clip until the crew is back on solid ground. “Everything checked out,” says Matt Kendall as he steps off. “I’m a little sore and my hands feel tight, but everything’s good. A good climb.”

The crew gathers for a quick discussion about how it all went. They talk about what they saw, what they put their hands on, and key takeaways from their findings. They communicate in a way only climbers understand, noting nuanced changes in the performance of their gear and the complications of the experience at 150 feet. The exhilarating feeling of achievement they share is hard to describe. You kind of had to be there.

“One really big benefit of our work is you never stay in one place too long,” explains Outman, gazing up at the steel structure. “There are no typical days at the office. There’s no office! And you’ve got great views of the world that really make you feel like your work time is time well spent.”

The thrill of the climb and the breathtaking beauty of the landscape are two benefits Outman promotes in the ongoing search for the right people to join Commenco’s tower service team. Good climbers are hard to find but we’ve had some pretty good luck landing them because our work is unique and specialized, and we take good care of our people.

There are crews who build towers and others directly employed by giant communications companies. But there just aren’t too many businesses like ours offering service that blankets the tower environment, from the nearby buildings housing mechanical support systems, to the incandescent bulbs at the top now being replaced by LEDs, and all of the technology in between.

“Commenco’s been scaling towers for public radio systems since the 1950s. We not only know how to climb, we also understand all of this equipment and how to take care of it,” says Outman, peering over his glasses, as his crew unbuckles gear, wipes away sweat and packs up the truck. “It’s very exhausting, difficult, on-task work both mentally and physically. And we take a lot of pride in doing it well.”